Sugar: The Flavour Carrier

Sweet – the most important taste element Welcome to the fourth in my series of articles on taste, flavour and their importance in the art of cocktail creation.

21 November 2022 · 15 min read

Over the next few issues, we’re going to get into the detail of the primary taste elements associated with cocktail creation, namely: sweet, sour and bitter (sorry salt and umami lovers). We will explore what they are, work through the exact purposes they serve, and find out how best they can be employed to elevate your mixed drinks to the next level. There’s really only one place to start, and that is with the that sweet little thing we call sugar. In our craft, sugar is without a doubt the most important taste element. It is also by far the most widely utilised. And, commonly, the most misunderstood. Sugar serves multiple purposes in cocktails. Most obviously, it adds sweetness, but it also adds body and texture. It can be used as a preservative to enhance the shelf life of fresh ingredients. It is water soluble so can be transformed into easy-to-use syrups. It can absorb hard-to-extract flavours such as citrus oils, but most importantly of all sugar carries flavour. I know I’ve said this a few times already in my previous pieces but it’s worth repeating as this fact is often overlooked by

THE UBIQUITY OF SUGAR

Have a think about all the cocktail recipes you know; I’ll bet nearly all of them include a sweet element of some sort, either in the form of a syrup, liqueur, or modifier. I’d go as far to say that well over 99.9% of all the recipes out there do, and in fact, off the top of my head, I can only think of three well-known cocktails that don’t contain any sweetener at all: the Dry Martini Cocktail, the Mizuwari and the Vodka Soda.

Before you @ me on any of these drinks, I know there are slight issues with all of them

- There is a small amount of sugar in dry vermouth but, in my opinion, not enough to be perceptible in a Martini.

- The Mizuwari is technically only two ingredients (whisky and water), but it takes a high degree of skill to make a good one so I’m classing it as a cocktail.

- Is a Vodka Soda a cocktail? With a squeeze of lime, I would say it is. And yes, there is some sugar in lime juice, but I refer you to my point on the Martini.

So, why am I highlighting them? Well, aside from being the only ones I can think of (if you know any others, please let me know in the comments section below), they all rely on triggering our trigeminal sensations (temperature, texture, intensity etc.) over their flavour to make them enjoyable. While all three of course need to be ice, ice cold, they are also dependent on their alcoholic and textural intensity:

- The perfect Dry Martini Cocktail needs a high ABV to give it its signature strength and viscosity.

- The Mizuwari requires an impeccable balance of whisky and water with robust blocks of ice to maintain its dilution levels.

- The Vodka Soda is at its best when the water is highly carbonated, with the effervescence adding a different layer of textural intrigue.

In short, cocktails that do not contain a sweet element of any sort are characterised far more by their trigeminal qualities rather than their flavour. Why? Because – let’s say it one more time, with feeling – sugar carries flavour.

THE MISUNDERSTOOD TASTE

I’ve sat through countless menu development sessions over the years, tasting and tweaking the cocktail offerings of my teams to get them to the stage where they can go on the list. In this process, the one thing I’ve noticed above all is that there is a reluctance among modern bartenders to use the appropriate amount of sugar in their cocktails. There are numerous reasons for this – the demonisation of sugar from a dietary perspective being a common and valid one. But I think the primary driver, which is often in no small part down the ego of the creator, is worrying about making drinks ‘too sweet’., There is a mindset that sweeter drinks lend themselves better to an ‘unrefined’ palate, therefore bartenders want to demonstrate their taste maturity by making drinks which are sharper and dryer. There is, of course, some truth in this: as we age our palates and flavour preferences change. However, rather than improve the flavour, cutting back on sugar in fact has the opposite effect of decreasing flavour intensity and offsetting balance. Many bartenders I’ve worked with, when trying to fix an unbalanced or insipid creation, will often take to adding more and more ingredients or employing different mixing techniques in search of a solution, making their drinks increasingly complex and difficult to make. Nine times out of ten all they need is one extra bar spoon of sugar syrup. Sugar, when used correctly and in sync with other taste elements, should not present itself as sweet, it should be balanced, harmonious, and fulfilling its primary role as a flavour enhancer.

THE LEMONADE EXPERIMENT

To best demonstrate this, we need to do a little experiment, one you can do at home. You will need:

- 25ml (1oz) 1:1 sugar syrup

- 25ml freshly squeezed lemon juice

- 25ml water

First off, I want you to taste each component individually, a tiny sip will do. The syrup will be sweet, the lemon juice will be sour, and the water will, well, be like water. No real shocks there. Next, I want you to pour them all into one glass, give them a quick stir, and taste again. What do you get this time round? Well, all things going to plan, you should be hit with the overwhelming flavour of lemon. So why couldn’t we taste the flavour of lemon in the lemon juice? The interesting thing is that while the lemon element was there all along in the form of aroma molecules, it just didn’t have a vessel to turn them into flavours. Lemon juice does of course contain some sugar (about 2.5 grams per 100 grams of juice) but not nearly enough for it to have a meaningful flavour when consumed alone. That’s where the sugar comes in and works its magic.

WHAT IS SUGAR?

Sugars, in their simplest form, are short-chain carbohydrates that our bodies use for energy. These carbohydrates are naturally occurring molecules, found in all types of food. They are made up of different arrangements of hydrogen, oxygen, and carbon, and the four we are going to focus on are:

- Glucose – our body’s main source of energy, found in some form in nearly all food types.

- Fructose – as the name suggests, fructose is the primary sweetener in most fruits and also honey and agave syrups.

- Sucrose – more commonly known as ‘table sugar’, sucrose is the most commonly found refined sugar and the one favoured by nearly all bartenders (with good reason). It occurs naturally in sugar cane and sugar beet.

- Maltose – derived from grains and cereals and generated during the beer and whisky making processes. It is also found in fruits such as pears and peaches.

There are many natural products that we think of as sugars – such as muscovado or palm sugar – which get their distinctive flavour from the raw ingredients from which they are sourced. There are also synthetic sugars – like the much-maligned aspartame – which have been developed to serve specific purposes in the food industry, but we’ll leave these for another day.

MONOSACCHARIDES VERSUS DISACCHARIDES

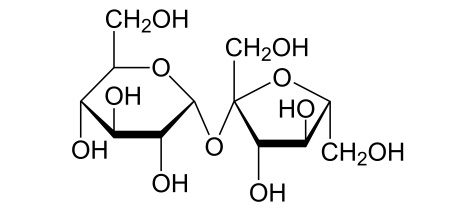

This is where we get a bit nerdy… These four basic sugars we focus on – glucose, fructose, sucrose, and maltose – can be further broken down into two subcategories: monosaccharides and disaccharides. Monosaccharides consist of a single sugar molecule made up of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen. They are the simplest form of sugars and the easiest for our bodies to break down and convert into energy. Glucose and fructose are examples of monosaccharides. Disaccharides, however, consist of two monosaccharides fused together. So, sucrose is a disaccharide made up of a glucose molecule and a fructose molecule, while maltose is made of two glucose molecules.

INTENSITY, LENGTH, AND THE GENIUSES AT CRUCIBLE LONDON

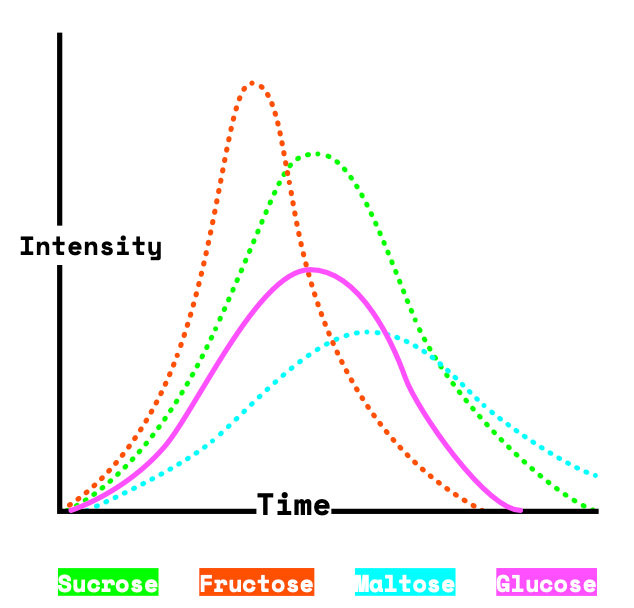

Why is this important? Good question! Each of these sugars has a different intensity of sweetness and also differing length of time that the sweetness lasts on the palate. Understanding both how sweet they are and how long that sweetness will last in our drinks is crucial in choosing the right sugar for specific cocktails. Luckily for us, my good friend Stu Bale, founder of the world-renowned creative agency Crucible London and all-round drinks genius, has done a huge amount of work in the study of sugars, and has created this handy graph that explains it far better than I could hope to.

As you can see, the sweetest of all sugars is fructose, it also has a bright, zingy freshness to it. Its sweetness doesn’t last particularly long on the palate so will die away quite quickly, and as its intensity drops off, so too will its flavour-carrying capacity. When we use fructose-heavy sweeteners, such as honey and agave syrup, we need to be wary of how sweet they taste at first as well as the faster finish of the flavour. Maltose, on the other hand, is the least sweet of the four but has by far the longest length of flavour. It also has the most distinctive flavour, offering a malted profile, as its name would suggest. Maltose, on the other hand, is the least sweet of the four but has by far the longest length of flavour. It also has the most distinctive flavour, offering a malted profile, as its name would suggest. Sucrose is where it gets interesting. As you can see, sucrose, or white sugar as you probably know it best (whether granulated or the finer-milled and faster-dissolving caster sugar), has both a high intensity of sweetness and a long-lasting flavour. It is the most ideally suited of all the sugars for making drinks as it sweetens and carries flavour incredibly well. But that doesn’t mean it can’t be improved upon.

COMBINING SUGARS TO MAXIMISE QUALITIES

As mentioned, the problem with using high-fructose sweeteners like honey or agave syrup is that while they have an incredible flavour of their own, when we use them in cocktails their sweetness spikes early then dies off, meaning that both their flavour and the other flavours they should be enhancing, will die off as well. An easy way to combat this is to cut them with caster sugar syrup. This will allow the honey or agave to take on the lengthening quality of the sucrose, but crucially won’t dilute the flavour as the sucrose will serve its primary role as a flavour enhancer. This is a more manageable and easier way to use syrup, and on top of that reduces the cost, allowing you to use more expensive and exotic ingredients without compromising on flavour quality. We can take this even further and apply it to nearly all classic cocktails (as well). The most innovative use of sugars I’ve encountered was by Marcis Dzelzainis, founder of Idyll Drinks, while he was working at Mission in Bethnal Green, London, many years ago now.

Marcis used sugar like a chef would use stocks, using different types with the additions of tiny amounts of ‘seasoning’ to boost and enhance the signature flavours of his cocktails. He made two varieties of sugar syrup, one for citrus-led shaken drinks like Daiquiris and another more suited to stirred-down classics such as Old Fashioneds. It was revolutionary at the time but if you think about it, it makes perfect sense; why should we use the same type of sugar syrup for such wildly different styles of drinks? Both his syrups serve the same overall purpose of sweetening and carrying flavour, but they do it in a different way. His ‘Bright Syrup’ for Daiquiris and the like was a mix of fructose and sucrose, with a tiny amount of orange blossom to act as a seasoning element. It gives an initial intense hit of fresh sweetness from the fructose that then lingers, allowing you to boost the citrus content to balance the increased sweetness, leading to a fresher, brighter cocktail. His ‘Dark Syrup’ for stirred down style drinks combines sucrose with a small amount of maltose and a tiny hint of vanilla. This is perfectly suited to stronger, dryer styles of cocktail as it dramatically lengthens the flavour but without increasing the sweetness, leading to an incredibly elongated flavour profile that is simply not achievable with conventional sugar syrup. I think we can agree there’s much, much more to sugar than just the sweetness. Next time round we’re going to go in depth on our sour senses, and see just how important acidity can be.

———— The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Freepour.